I was deaf and didn’t know it. When I was in my late twenties, I went in for a hearing test just to see how bad my hearing really was because I had noticed some changes after getting married and having children. I didn’t always hear them at night, couldn’t hear the smoke alarm after setting it off with burned food, and a few other things.

At that time, they told me I had a 90% high-frequency hearing loss. I didn’t know exactly what that meant, but I mostly discounted it as minor since I was getting along fine. I did legal transcription work at the time, and if it was so bad, how was I good at it?

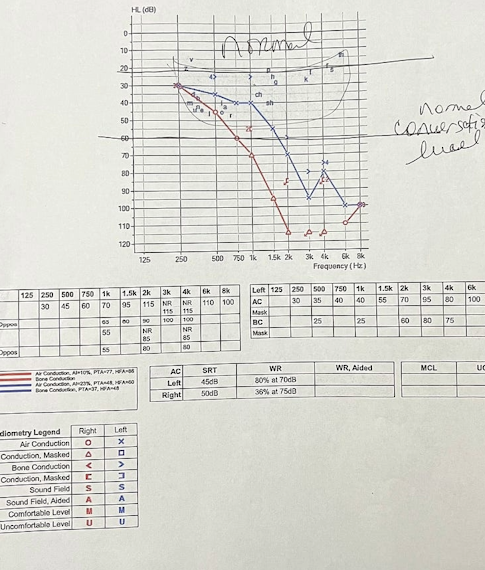

Some thirty years later, I had another hearing test and exam, and the audiologist explained exactly what the numbers meant. She told me that my hearing loss was due to excess scar tissue, likely caused by repeated ear infections when I was a baby, years before ear tubes were a common solution. The results of that test showed that normal conversation falls completely above the line of what I can hear in my right ear.

I specifically cannot hear higher-pitched sounds like s, f, ch

I specifically cannot hear higher-pitched sounds like s, f, ch (basically all the consonants). Worse than that, though, is how they measure my word recognition, which shows that my right ear recognizes 36% of spoken words no matter how loud they are yelled at me. I’d spent a lifetime never knowing what I missed or that I had even missed anything.

My parents tell a story from when I was about two or three years old. They had a guest who was bouncing a quarter off the floor while they were talking. I was sitting with my back to them, playing and paying no attention. After a bit, the man told my parents I must be hard of hearing because not once did I acknowledge the “thunk” of the quarter at any time, even though others noticed it.

Like most parents, their first reaction was to be offended that someone said something negative about their child. I know that feeling because I experienced it myself when a friend commented on our son’s crooked feet after he was born. They were, and our baby wore casts for months, but it still stung. It truly brings out the momma bear to hear negativity about your child, and I have no doubt my parents felt the same way.

I never knew I was hard of hearing in school. Teachers mistook confusion for inattention and talking for misbehavior, so they moved me to the front of the room for behavior. It worked well enough. I got good grades in everything (except math and most science classes and penmanship) and I read far above my level. I was unconsciously learning to translate the world through sight instead of sound by reading faces, lips, and timing instead of tone.

In hindsight, that same kind of compensation extended to my social life. I usually had one friend at a time through school, probably because I could “hear” and communicate with just one person. I didn’t flourish in a group setting. Still, I loved hosting get-togethers and was an attentive hostess, though a lot of what went on around me passed by unheard.

In my early teens, I wanted to sing so badly they finally let me try a solo. I sang The Royal Telephone, an old hymn, and it was awful. People still remember it, and I’m sixty now. I was never asked to sing another solo at the church in Sulphur Rock, but I did keep singing. After that, I stayed in the choir, safely tucked in the middle. My singing, after high school, changed throughout the years, for all its flaws, I felt like a blessing, to others and to myself. It was never perfect, but it was blessed.

During that same time frame, my parents bought an old harvest-gold upright piano. I was so excited to learn to be like Regina, a beautiful young lady who played and sang at church, so I taught myself to read music and play badly, but well enough, by God’s grace, to fill a need in the church my dad pastored when I was eighteen. My music was mostly visual since I changed keys when the guitarist changed keys; the congregation was patient and paused during complex key changes, so it was a case of some music better than no music, but it worked out! No one was happier than I was when a real pianist moved to our church!

The lack of crisp consonant distinction had impacted my ability to help my daughter when she was a child. The school noted she had a lisp and attended speech therapy. I was unable to help her because I literally could not hear the lisp.

My work life didn’t match any of this. For years I was the friendly drive-through voice at McDonald’s and Wendy’s, the one they sent to other stores when inspections rolled around, all while I was still in college. Through the years, I completed multiple degrees, worked in customer-service jobs where I interacted with people both in person and on the phone, and even taught face-to-face classes in college. I honestly thought I was just good at multitasking and reading people, but the truth was, my brain had been filling in the gaps where my ears failed me. After hearing the audiologist tell me none of this should have been possible, I look back in awe at something I thought was just normal everyday life.

Of all the ways my hearing loss has shaped my life, marriage has been the most revealing. They say opposites attract, and if my hearing is bad, his is almost superhuman. We can’t whisper about him in the same house without him hearing, yet I’d miss an “I love you” unless it was shouted. Before the diagnosis, he was endlessly frustrated, trying to translate my half-heard responses and make sense of the silences between them. Now that I have ears and we understand the extent of it, we’ve both had to adjust. He watches TV with closed captions so I’m not constantly asking what was said. I still miss the softer things, like when someone’s voice drops to say something tender or private. Those are the ones that slip past. But he’s learned patience, and I’ve learned to own my ears. We’ve been married since 1990, and after all these years, we’re still learning how to listen to each other and to the quiet in between.

I didn’t get “new ears” until my late forties, and I hate calling them hearing aids because that feels like I’m a hundred (no age shaming). In my late forties I finally went back for another test after seeing ads for digital ones. Insurance would cover part of them, and I had started noticing how much I was missing during family gatherings. Turns out, my hearing had barely changed over all those years. My new ears are small and black, and I hope people assume they’re earbuds. It’s a little funny that if one of them dies while I’m wearing it, that ear becomes completely blocked and I hear absolutely nothing, and it takes me a bit to notice I’m deaf.

One day while I was inspecting a house for an appraisal, I was on the phone with my spouse. I had had the new ears only a few days. While walking around the house, I heard this odd slapping noise, when I reached the back of the house I realized it was waves hitting the dock. After a lifetime of living on the lake and inspecting lake homes, I had never heard the sound of water lapping. I stopped and stood there as I heard something so normal, so every day, and recognized I’d never heard that or heard the birds, faucets dripping, the cat’s meow… simple things most people don’t think twice about. I found myself just trying to identify every sound. I was in a kind of awe. Maybe even the realization that I’d missed more than I ever realized.

Even my car makes noises I didn’t know existed, and for the first time in my life I can actually hear the smoke alarm. I still can’t always hear Sheba or Cleo meow unless I see them moving their tiny mouths. Since getting the ears, I’ve learned they don’t fix everything, and some things are worse. The screech of tiny shrill voices, the noise overload at the grocery store, and the surround sound on the television—those are the kinds of days when it feels like life is turned up to eleven on the ten scale.

I still have to watch people while they talk; ears alone are not enough, and I still have to ask students to repeat themselves, repeatedly. By the time I get home from a day of hearing, I’m ready to pull my ears off and welcome the sound of life turned down.

For years I wore my hair so it would hide my ears, ashamed that I couldn’t hear and unwilling to admit it, like it was a flaw. Now I pull my hair back, and let people think what they want. I’m not sure if I’ve accepted them or accepted who I am and no longer care what others think. The world is rougher and richer, alive and loud in ways I never knew it could be.

As a child the story of Helen Keller moved me. She had a rich full life without sight or sound. I found myself empathizing with her, not realizing that in my own limited, nowhere-near-comparison life, I too managed.

I only decided to tell this story because of a VA audiologist I met during a home inspection. She noticed my ears and asked about them, and I told her a little bit of what I’ve told here. When I mentioned hearing the lake for the first time, she smiled and said people like me remind her why she does her job. That stuck with me. After years of hiding my ears, getting them when I was nearly fifty and barely wearing them, it finally felt like it was time to stop hiding. These new ones are programmed exactly for what I need. My hearing still isn’t normal but it’s better, and for now, that really is enough.

If you’re reading this on my website:

This story was originally published on my Medium page, where readers can comment, clap, and share their own experiences. You can join the conversation here: [link to Medium post]

If you’d like something lighter after this piece, you might enjoy my humorous birth story involving a very ill-timed haircut:

https://vickysview.com/funny-birth-story-haircut-labor/

For more information about hearing loss and related conditions, the Mayo Clinic provides an excellent overview:

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hearing-loss/symptoms-causes/syc-20373072

📬 Follow Vicky’s View

Subscribe for fresh posts from the desk of Vicky — AI tools, storytelling, odd moments, grandkid wisdom, and whatever else stirs up trouble (or inspiration).