📜 About This Project

I was honored to be one of 50 contributors selected from over 500 applicants for the Smithsonian and U.S. Postal Service’s Indians at the Post Office project. My piece, Last Home of the Choctaw Nation, was accepted for publication and remains part of the project’s archival collection—even though it was never publicly released due to image licensing restrictions.

By Samantha V. Edwards, M.S.E., M.A. – Contributor, Smithsonian/USPS Indians at the Post Office Project

Introduction to the Mural and Its Journey

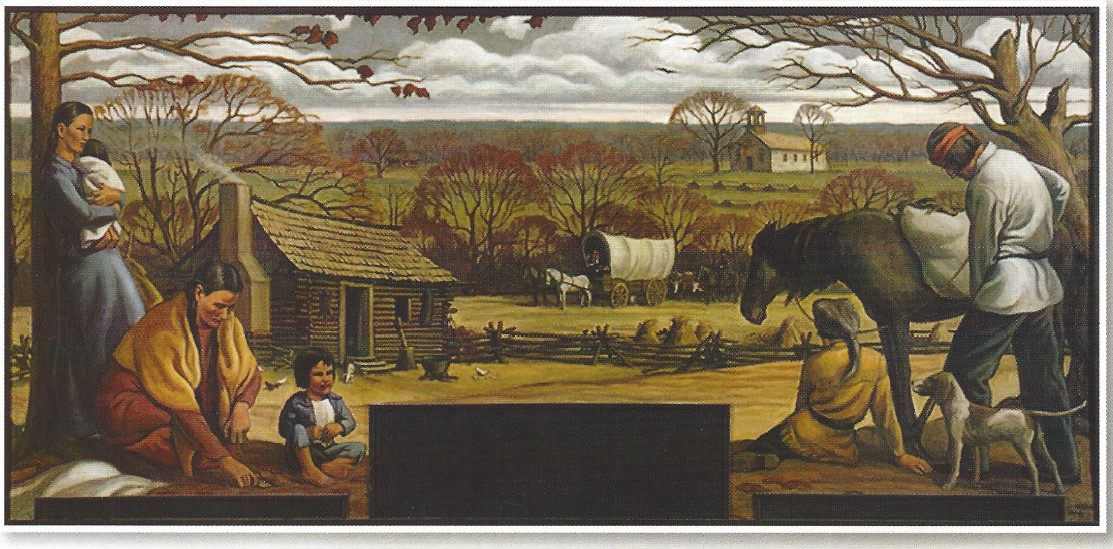

H. Louis Freund’s “Last Home of the Choctaw Nation” (1940) is an oil-on-canvas mural that was commissioned by the United States Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts during the Great Depression. This Choctaw Nation mural was previously displayed in 1940 in the now closed Idabel OK post office. The three notches at the bottom of mural are from the original installation and accommodated the door to the postmaster’s office and two bulletin boards. When the Idabel post office relocated to the Federal Building, the canvas was mounted on plywood and displayed at the new location behind the main customer counter. During the early 1990’s the Federal Building underwent significant renovations which did not provide for the display of the mural. As a result, the canvas was moved to the Museum of the Red River in Idabel, Oklahoma. The museum had the mural conserved and cleaned by Anton Rajer of Madison, Wisconsin in 2001. (Vick)

Symbolism and Story Within the Mural

The mural depicts a Choctaw homestead, circa 1880 in McCurtain County, Oklahoma, which sits within the boundaries of the Choctaw Nation. As is typical of the Choctaw, the log cabin is well cared for and the homestead has the trappings of a prosperous farm land as evidenced by the fence marking the land boundaries, chickens, pets and multiple horses and cattle. The seven Choctaw depicted in the mural are a family unit. The woman on the left side of the mural is digging snake root. The men of the family appear to be preparing to journey, perhaps to trade snake root or other items. The presence of the covered wagon and pack horse in the background is most likely a reference to the traders that traveled through the area. (Freund) In the far right background is the Wheelock Church, a Presbyterian Mission built in 1846, which is still standing today and is the oldest church in the Choctaw Nation. In front of the church, although not clear in the mural, are traditional burial structures that cover Choctaw graves. “I am using a rather bleak landscape to symbolize the dying out of the tribe.” (Freund) Considering the murals predominate colors are indigenous to the Oklahoma terrain, the gravesite serves to emphasize the bleakness of the area and the dying of the Choctaw tribe.

The Choctaw Nation’s Removal and Resilience

The Choctaw ceded over ten million acres before being removed from their tribal lands. The emigration spanned a three-year time frame whereby nearly 15,000 Choctaws moved to what is now known as Oklahoma. Not all of the Choctaws made it too their new home; nearly 2,500 of them died in route along what became known as “The Trail of Tears.” Principal Chief George W. Harkins, chief of the Apukshunnubbee District of the Choctaw nation, denounced the removal of the Choctaws in a widely published letter to the American people, in which he stated,

“It is with considerable diffidence that I attempt to address the American people, knowing and feeling sensibly my incompetency; and believing that your highly and well improved minds would not be well entertained by the address of a Choctaw…We were hedged in by two evils, and we chose that which we thought the least….We go forth sorrowful, knowing that wrong has been done.… If they suffer, so will I; if they prosper, then will I rejoice. Let me again ask you to regard us with feelings of kindness.” (Harkins)

After the Choctaws became acclimated to their new home, recovered economically and rebuilt their homes, as well as their pride, they also attempted to repair their relationship with government entities. “They re-established their constitutional republic in 1834. By 1836, there were eleven elementary schools in the area. Nine high school-level institutions were started, including Wheelock Academy, which opened in 1842 west of Idabel. By 1848, Choctaw newspapers were in circulation, and Christian missionaries had been given permission to establish new stations in the territory.” (Choctaw) Eventually, Choctaw Christian ministers outnumbered their white counterparts as the church became the focal point of their community life. Despite Freund’s visualization of a dying tribe, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma continued to grow and thrive while achieving economic success and preserving the history and fundamental elements of their culture as a vibrant, active tribe in the 21st century. (Kidwell)

About the Artist: H. Louis Freund

Born in Clinton, Missouri on September 16, 1905, H. Louis Freund was inspired to become an artist by various family members. He became a muralist famous for his depictions of life in the Ozark Mountains in Arkansas during the 1930’s. He championed the arts throughout his life and was instrumental in establishing art departments at two colleges in Arkansas and one in Florida. In addition, along with his wife, he founded the Summer Art School in Eureka Springs, Arkansas. Freund began competing for mural commissions at the federal Treasury Section of Fine Arts around 1932 while working as an artist in New York. He traveled through both Arkansas and Missouri researching and recording the native cultures of the areas. He painted six large murals on post offices in Herrington, Kansas, Windsor and Clinton, Missouri, and in Pocahontas, Heber Springs and Camp Chafee, Arkansas. Freund contributed paintings and art work throughout Florida, Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas and Missouri. He reportedly sent over 100 paintings to Washington DC.

Freund’s style sought the emotional aspect of his subjects by using dramatic heavy outlines and somber colors. He was known to paint in the early Renaissance style he studied during his education in Paris at the Colarossi Academy and La Grande Chaumiere using the methodology of compressing time and space elements in order to capture a broad timeframe in a cohesive moment. Freund died on December 22, 1999 and is buried in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

🪶 What Does This Mural Say to You?

💬 Art preserves more than paint—it carries memory, meaning, and truth.

If this mural or story moved you, inspired a memory, or made you see something differently, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

👇 Share your reflections in the comments below.

Works Cited

Bell, Jesse S. American Native Press Archives and Sequoyah Research Center. n.p. Web. 15 September 2015.

Choctaw, The. Liberty Park USA. 2005. Web. 21 September 2015.

Freund, H. Louis. Letter to Mr. Edward B. Rowan. 15 Nov. 1939. MS. N.p

Elder, Tamara. “New Deal Murals in Oklahoma.” Oklahoma: Magazine of the Oklahoma Heritage Association (2000): 15-21. Print.

Harkins, George W. Sequoyah National Research Center. n.p. Web. 15 September 2015.

Kidwell, Clara Sue. “Choctaw Tribe.” n.d. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. 28 July 2016. <www.okhistory.org>.

Vick, Daniel L. The Mary H. Herron Keeper of Collections Samantha Edwards. 29 September 2015. Correspondence.

📬 Follow Vicky’s View

Subscribe for fresh posts from the desk of Vicky — AI tools, storytelling, odd moments, grandkid wisdom, and whatever else stirs up trouble (or inspiration).