Practical Tools, Ethical Strategies, and Classroom-Ready Tips for 2025

By The Mechanical Muse (edited by Vicky)

The question isn’t whether students will use artificial intelligence—it’s how they’ll use it. In a world where a full-fledged essay draft is only a prompt away, our role as educators is undergoing a profound shift. We can either try to block a signal that is already everywhere, or we can teach our students how to tune it, filter it, and use it to make their own thinking clearer and sharper.

This guide to using AI in the classroom provides a comprehensive framework for teaching students to use AI not as an answer machine, but as an intelligent research partner. We explore the historical context that makes this moment unique, introduce a new mindset for digital-era verification, and provide practical strategies for using AI to foster the one skill that can’t be automated: critical thinking.

Table of Contents

- Getting Started with AI: A Teacher’s Primer

- What is Generative AI?

- The Evolution of Research: From Dewey to Dialogue

- The New Mindset: From Search Engine to Synthesis Engine

- The Prompt Ladder: A Framework for Deeper Inquiry

- AI as a Critique Partner: Strengthening Student Arguments

- Human-First Synthesis — Building Your Argument

- Policy and Integrity: The “Disclose and Describe” Model

- Managing Assessment and Workload in the AI Era

- Equitable AI Literacy and Final Thoughts

- Sources for Further Reading & Classroom Resources

1. Getting Started with AI: A Teacher’s Primer

What You Need to Know About AI

- Choose a Tool: Start with free, reputable platforms like ChatGPT or Claude. Check with your institution for approved tools.

- Sign Up: Create an account using your email. Use institutional emails when possible.

- Test a Simple Prompt: Try something basic like, “Explain photosynthesis in simple terms.” Check for accuracy and tone.

- Explore Features: Try summarizing a PDF or generating discussion questions. Use available tutorials.

- Practice Verification: Confirm outputs with reliable sources (e.g., academic journals, archives).

-

Anthropic provides Claude walkthroughs at anthropic.com/support.

-

Search Edutopia (edutopia.org) for classroom-focused AI videos tailored to educators.

-

Hallucination: When AI generates false or invented information, like a fabricated quote or date.

-

Prompt Engineering: Crafting specific, clear instructions to get useful AI outputs (e.g., “Summarize this article in 100 words” vs. “Tell me about this article”).

-

Training Data: The vast dataset of texts AI uses to generate responses, which may include biases or outdated information.

-

Context Window: The amount of text an AI can process at once (e.g., Claude’s large context window handles longer documents).

2. What is Generative AI?

Generative AI refers to computer systems—like ChatGPT or Claude—that can produce original content based on prompts from users. Unlike search engines that direct you to existing documents, generative AI can write essays, summarize arguments, simulate dialogue, and suggest ideas on demand. These tools are trained on massive datasets, meaning they “synthesize” patterns in writing—but they do not know facts. Their output must always be verified.

Think of generative AI as a highly imaginative assistant: it works fast, but it doesn’t always tell the truth. The goal is not to ban it, but to learn how to use it with discipline and skepticism.

Why this matters: Knowing the difference between a search engine and an AI is like knowing the difference between a library and a creative brainstorming partner. You go to the library for facts you can trust; you go to the partner for new ideas. Using the wrong tool for the job leads to weak arguments and factual errors. This skill helps you get the right kind of help at the right time.

Search Engines vs. AI: Two Different Tools for Inquiry

The roles of search engines and AI differ dramatically in the research process. While search engines retrieve existing content, AI synthesizes, predicts, and generates new responses based on its training data.

| Feature | Search Engine (e.g., Google) | Generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT) |

|---|---|---|

| Input | Keywords, questions | Keywords, questions, full paragraphs, documents |

| Process | Indexes and retrieves existing web pages | Predicts the next word based on patterns in its training data |

| Output | A list of links to existing sources | A new, original text, image, or code |

| Source Transparency | High (provides direct links) | Low (often synthesizes without attribution) |

3. The Evolution of Research: From Dewey to Dialogue

Understanding where research comes from helps students appreciate why AI tools aren’t a replacement—but an evolution. Below, we break down the time, tools, notes, and mindset of each era.

🕰️ Pre-Internet Era (Before ~1995): Characterized by immersive reading and deep memory retention but limited by physical access. Research was a slow, deliberate process of engaging with sources from trusted publishers, encyclopedias, and archives. It involved extensive physical notetaking—jotting down quotes by hand, organizing index cards, and summarizing passages from books and articles.

💻 Internet Era (c. 1995–2022): Marked by global access and diverse perspectives. The challenge shifted from finding sources to filtering them, leading to skills in evaluating credibility but also the risk of information overload and surface-level skimming. Students combined traditional notetaking with digital shortcuts—copying and pasting sources into Word documents and using citation management tools like Zotero or Mendeley.

⚙️ AI Era (2022–Present): Defined by speed and synthesis. AI offers incredible support for brainstorming and structuring ideas, but introduces the critical new challenges of intellectual laziness, fabricated “hallucinations,” and the need for rigorous, manual verification. In this era, students must learn to craft effective prompts, cross-check AI output for accuracy, and integrate it with trusted, verifiable sources.

This evolution fulfills the vision of educational philosophers like John Dewey, who emphasized inquiry over the passive reception of information. The shift from a simple search to a critical synthesis mirrors his call for reflective, experiential learning. Teaching students to question, verify, and reflect aligns directly with Dewey’s philosophy of education as preparation for thoughtful participation in a democracy.

For Instructors: Timeline Activity

- Objective: Students will be able to compare historical research methods to articulate how the skills of inquiry have evolved.

- Estimated Time: 30 minutes

- Materials: Whiteboard or digital collaboration tool (like Jamboard or Miro).

- We Do: As a class, collaboratively build a timeline with three columns: Pre-Internet, Internet, and AI Era. Ask students to populate each column with the tools, skills, and challenges they associate with it.

- You Do: Assign a short reflective prompt: “What is one research skill from a past era that is still essential today, and why?”

- Scaffolded Option: Provide a pre-filled timeline template for students to label and expand upon.

- Evidence of Success: Students accurately compare research eras and justify at least one enduring skill.

- Why this matters: Understanding how research was done before Google and AI shows that the tools change, but the core skills don’t. Skills like careful reading, organizing ideas, and questioning sources are timeless. This perspective helps you see AI not as a replacement for thinking, but as one more powerful tool in a long history of human inquiry.

4. The New Mindset: From Search Engine to Synthesis Engine

The most critical shift for students to understand is that an AI is not just a fancier Google. A search engine finds containers of information (articles, books, videos). An AI, however, is a synthesis engine. It opens those containers, mixes the contents together, and presents a new concoction, often without a recipe or list of ingredients. This breaks the chain of provenance and demands a new level of skepticism.

Teach students to treat AI-generated text like a rumor from a very intelligent, well-read, but occasionally dishonest friend. Their first instinct must always be: “Can you prove it?” To do that, they need a concrete process.

The Verification Workflow: A 3-Step Process for Students

- Isolate the Claim: Break down the AI’s paragraph into individual, testable facts.

- Triage the Claim and Choose the Right Tool: Use the right method depending on whether the claim is a quote, fact, or cited source.

- Consult the Source Hierarchy: Evaluate the quality of your evidence by consulting a tiered system of source reliability.

The Source Hierarchy Explained

Not all sources are created equal. Teach students to evaluate evidence by placing it within a hierarchy of trust.

- Tier 1 (Highest Trust): Peer-reviewed academic journals, university press books, and data from government or scientific agencies (e.g., NASA, NIH). These sources have undergone rigorous expert review.

- Tier 2 (High Trust): Reports and articles from major journalistic outlets with strong editorial standards (e.g., The Associated Press, Reuters, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal).

- Tier 3 (Medium Trust; Use with Caution): Reports from well-regarded think tanks or non-profits, expert blogs, and professional organizations. These can be valuable but may carry a specific agenda and require cross-verification.

- Tier 4 (Low Trust; Use for Background Only): Wikis, unverified websites, social media, and user-generated content. These should never be used as the primary source for a factual claim in academic work.

For Instructors: Fact-Checking Workshop

- Objective: Students will be able to apply the 3-step Verification Workflow to identify and debunk fabricated information in an AI-generated text.

- Estimated Time: 45 minutes

- Materials: A pre-selected, 300-word AI-generated text with at least three distinct errors.

- (I Do – 15 min): Model the verification process on a fabricated quote using the Source Hierarchy.

- (We Do – 20 min): Students verify additional errors in groups and document their steps.

- (You Do – 10 min): Groups report findings and reflect on the importance of this method.

- Why this matters: In a world filled with misinformation, the ability to verify claims isn’t just an academic skill—it’s a crucial life skill for being an informed citizen.

5. The “Prompt Ladder”: A Framework for Deeper Inquiry

To foster active inquiry, we must teach students to be intentional with their questions. The “Prompt Ladder” is a framework based on Bloom’s Taxonomy, a foundational concept in education that classifies levels of intellectual behavior. This model helps students climb from basic recall to complex, higher-order thinking.

Bloom’s Taxonomy Chart for AI-Powered Inquiry

| Level | Cognitive Skill | AI as a Tool | Sample Prompt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remembering | Recalling facts and concepts | AI as a Dictionary | “List the five most significant parliamentary acts that led to colonial discontent before the American Revolution.” |

| Understanding | Explaining ideas or concepts | AI as a Tutor/Explainer | “Explain the concept of ‘no taxation without representation’ as if you were a colonial merchant in 1765 Boston.” |

| Applying | Using information in new situations | AI as a Simulator | “Using the Boston Tea Party as a model of symbolic protest, design a non-violent protest a student group could use today.” |

| Analyzing | Drawing connections among ideas | AI as a Socratic Partner | “Contrast the roles of Enlightenment thinkers in the American Revolution with the roles of the working class in the French Revolution.” |

| Evaluating | Justifying a stand or decision | AI as a Devil’s Advocate | “Critique the argument that the American Revolution was a clear victory for liberty by considering the perspectives of enslaved people, women, and Native Americans.” |

| Creating | Producing new or original work | AI as a Brainstorming Partner | “Given these three counterarguments, synthesize a more nuanced thesis statement that acknowledges the complexities of the Revolution’s outcome.” |

For Instructors: Prompt Design Challenge

- Objective: Students will be able to compose prompts that elicit higher-order thinking by applying the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Estimated Time: 30 minutes

- Materials: A shared research topic (e.g., “the impact of social media on youth mental health”) and the Bloom’s Taxonomy chart.

- (I Do – 5 min): Teacher models writing one “lazy” (Remembering) and one “deeper” (Analyzing) prompt on the topic.

- (We Do – 15 min): In pairs, students write their own “lazy” and “deeper” prompts for at least three other levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- (You Do – 10 min): Pairs share their best “deeper” prompt with the class and explain which cognitive skill it targets.

- Why this matters: The quality of your answers depends entirely on the quality of your questions. Asking basic questions gives you generic, boring results. Learning to ask deeper, more analytical questions pushes the AI—and your own brain—to move beyond surface-level facts and explore the complex ‘how’ and ‘why.’ This skill will make your thinking sharper in every class, discussion, and future career.

6. AI as a Critique Partner: Strengthening Student Arguments

Beyond research, AI’s greatest power may be as a revision partner that fosters metacognition—the act of thinking about one’s own thinking. From a pedagogical standpoint, AI can act as a “More Knowledgeable Other” (MKO), a concept from psychologist Lev Vygotsky. The AI can temporarily provide the critical perspective needed to help a student advance through their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and improve their own work.

Encourage students to use these sample critique prompts on their completed drafts:

- “Read my thesis statement. What is the strongest potential counterargument?”

- “Analyze this paragraph. Identify any logical fallacies, weak evidence, or unsupported claims.”

- “What are three questions a skeptical professor would ask about the argument I’m making here?”

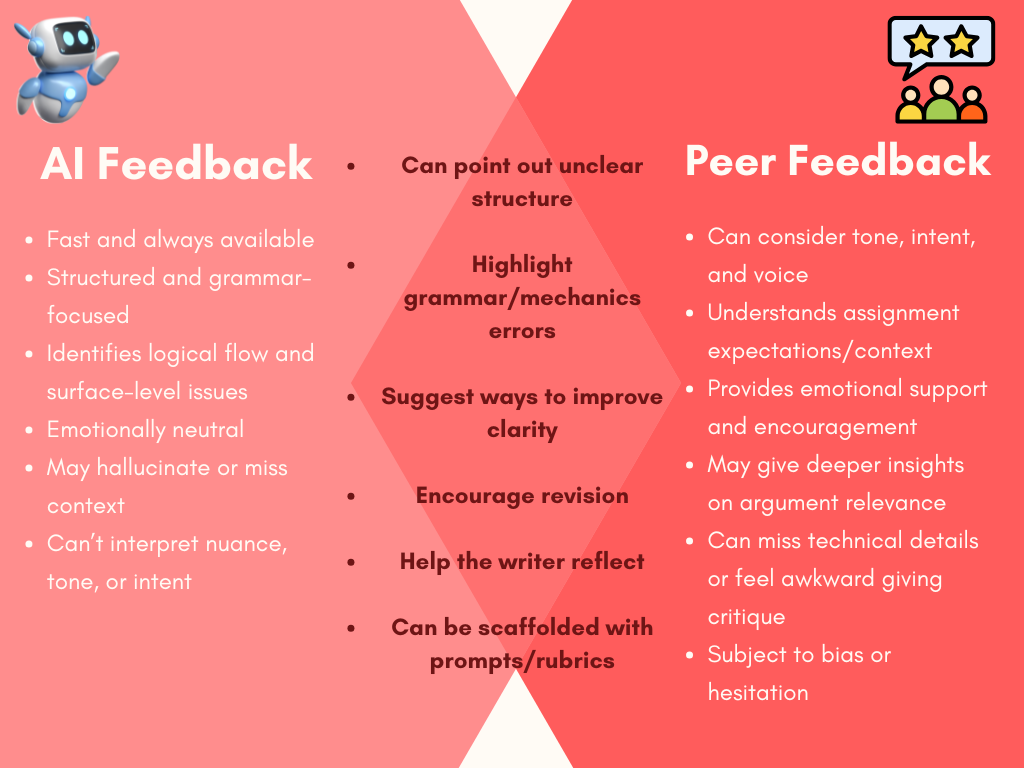

Comparison of AI and Peer Feedback Strengths

For Instructors: Peer Review with AI

- Objective: Students will use AI-generated feedback to reflect on and improve the clarity, structure, and support of their arguments.

- Estimated Time: 50 minutes

- Materials: A completed student draft essay.

- (I Do – 10 min): Students use critique prompts to have AI generate feedback on their own draft.

- (We Do – 20 min): Students exchange their paper and the AI feedback with a peer. The peer reads the paper, the AI’s comments, and then adds their own human feedback.

- (You Do – 20 min): Students get their paper back and write a short reflective journal entry: “Compare the AI feedback to your peer’s feedback. What was most helpful? What did the AI miss? What specific revisions will you make as a result?”

- Why this matters: Great ideas become stronger when they’re challenged. Using AI as a ‘critique partner’ is like having a private coach who can find the weak spots in your argument before anyone else does. This practice helps you build more persuasive, ‘bulletproof’ arguments and prepares you to confidently defend your ideas in class and beyond.

📝 Teaching Note 1: This activity doesn’t replace peer review—it enriches it. By critiquing the AI’s feedback, students begin to understand what helpful feedback looks like and why human insight still matters.

📝 Teaching Note 2: Remind students that AI feedback can sometimes be generic, overly focused on surface-level grammatical errors, or may misunderstand the core nuance of an argument. The goal is to use the AI’s critique as a starting point for their own reflection, not as a definitive set of instructions.

7. Human-First Synthesis — Building Your Argument

After using the Prompt Ladder to explore ideas and the Verification Workflow to gather trustworthy facts, the final and most important step is to synthesize this material into your own, unique argument. By this point, students have collected high-quality, verified facts—like ingredients laid out on a counter. But without synthesis, they risk falling into “patchwriting”: stitching together quotes and claims without forming their own voice. This step teaches students how to cook the meal, not just list the ingredients.

🔒 Closing the AI Window

Once research is complete and sources are verified, it’s time to shut the AI tab. From this point on, students should rely on their notes and thinking. The goal now is to build a human-first argument, using AI-assisted facts as support—not scaffolding.

📋 The Notes-to-Outline Method

Encourage students to use a synthesis table to organize and personalize their research:

| Verified Claim/Fact | Source(s) | My Analysis (How this supports my thesis) |

|---|---|---|

| The Dawes Plan was enacted in 1924, not 1923. | U.S. Dept of State Archives | This matters because it shows the plan was reactive, not preventive. That timing shapes my argument about ineffective postwar policy. |

| The quote “the only logical financial path forward” doesn’t appear in academic sources. | Google Books / JSTOR | The AI made it up. This shows why verification matters—and why my argument depends only on documented facts. |

Reminder: The facts are shared. The argument is yours.

Why this matters: This is the moment where your unique voice comes to life. Anyone can gather facts; your real value is in how you connect them to build your own argument. Closing the AI window forces you to move from being a collector of information to a creator of knowledge. This is what colleges and employers are looking for: not someone who can find answers, but someone who can build a unique perspective.

8. Policy and Integrity: The “Disclose and Describe” Model

Bans on AI encourage dishonesty. Transparent policies promote ethical use. This approach is more effective than an outright ban, which is often unenforceable and drives AI use underground. By encouraging transparency, we can teach the critical skills students need, rather than trying to police a technology that is already ubiquitous. Your syllabus should feature a clear policy that embraces AI as a tool while upholding academic integrity.

Sample Classroom AI Policy:

“AI tools may be used for brainstorming, outlining, and receiving feedback on your work. However, you must not submit AI-generated text as your own. For any assignment where you used an AI tool, you must include a brief disclosure statement detailing what tool was used and how it contributed to your process.”

Example Disclosure:

“I used ChatGPT to generate counterarguments to my thesis and to get suggestions for rephrasing two sentences in my conclusion for better clarity.”

Why this matters: Transparency builds trust and shows integrity. In any future career, using tools ethically is a highly valued skill. By disclosing how you used AI, you’re not admitting to a shortcut; you’re demonstrating that you are in control of your tools and confident in your own work. It’s the difference between hiding in the shadows and confidently standing by your process.

9. Managing Assessment and Workload in the AI Era

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the idea of checking every student’s AI use. But the goal is not perfection or surveillance — it’s building a classroom culture of honest, reflective, and responsible AI use.

🧭 Let Students Police Their Own Work

Require each student to document their process. For an assignment, ask for:

- Verification of one key AI-generated claim.

- The disclosure statement of how they used AI.

- A brief reflection on its usefulness and limitations.

Now you can scan for those behaviors across all papers — and spot-check one consistent element. You’re managing patterns, not hunting mistakes.

🧠 Assess the Process, Not Just the Product

Use the AI Disclosure and reflection as a learning artifact. A strong disclosure often says more about a student’s engagement than a polished draft.

Sample Rubric Component: Responsible AI Use (15 points)

| Criteria | Exemplary (5 pts) | Proficient (3 pts) | Developing (1 pt) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Disclosure | Disclosure is specific, clear, and accurately describes the tool and its contribution to the process. | Disclosure is present but generic (e.g., “I used AI”). | Disclosure is missing or inaccurate. |

| Verification | Student clearly documents the verification of a key claim, correctly identifying the source and outcome. | Student attempts verification but the process or source is unclear. | Verification step is missing. |

| Reflection | Student offers insightful reflection on the AI’s utility, limitations, and impact on their thinking. | Student reflection is superficial (e.g., “It was helpful”). | Reflection is missing. |

10. Equitable AI Literacy and Final Thoughts

AI literacy must begin with equity. Not all students have equal access to devices, reliable internet, or the background knowledge to use these tools effectively. As educators, we must be proactive in closing these gaps.

Equity in Action Checklist

- ✅ Survey Students: At the start of the term, anonymously survey students about their access to and comfort with technology.

- ✅ Use Free & Accessible Tools: When demonstrating, prioritize free, low-bandwidth, and highly accessible AI tools.

- ✅ Address Algorithmic Bias: Teach students that AI models are trained on human-generated data and can reflect societal biases. Ask: “Where might the AI’s perspective be limited or biased, and whose voices might be missing?”

- ✅ Protect Student Privacy: Advise students not to input personal, sensitive information into public AI models. Recommend using institutional accounts if available, as they often have stronger privacy agreements.

- ✅ Create Support Systems: Implement a “tech buddy” system pairing tech-savvy students with peers and partner with your school library or IT department on device loan programs.

The best AI tool is not the smartest one—it’s the one that helps students think better. Our task is to remain experts in thoughtful inquiry, not just tech trends. By preparing students to question, verify, and reflect, we are preparing them for the intellectual and ethical challenges of the AI era.

Why this matters: Technology is shaped by people and reflects their biases. Understanding that AI can have blind spots helps you question its output and seek out the missing perspectives. This critical awareness is essential for fairness and equity, preparing you to be a more thoughtful leader and collaborator in a diverse world.

11. Sources for Further Reading & Classroom Resources

- ChatGPT (OpenAI): A versatile tool for dialogue, summarization, and content generation.

- Claude (Anthropic): Known for its large context window (for analyzing long documents) and constitutional AI approach.

- Perplexity AI: A conversational search engine that provides answers with in-line citations.

Pedagogy & Educator Resources

- Dewey, John. Democracy and Education. 1916.

- ISTE | Artificial Intelligence in Education: iste.org/ai

- Edutopia | AI in the Classroom: edutopia.org/technology-integration/ai

- Common Sense Media | AI Literacy for Educators: commonsense.org

University Guidelines & AI Literacy

- Stanford University | Teaching & Learning with Generative AI: hai.stanford.edu

Citation & Style Guides

-

- MLA Style Center | How do I cite generative AI?: style.mla.org

- APA Style Blog | How to cite ChatGPT: apastyle.apa.org

📬 Follow Vicky’s View

Subscribe for fresh posts from the desk of Vicky — AI tools, storytelling, odd moments, grandkid wisdom, and whatever else stirs up trouble (or inspiration).